When a designer drapes fabric over a dress form and uses pins to secure smooth waistlines and three-dimensional hemlines, few people realize that this seemingly ordinary "human model" holds a thousand-year history of evolution in garment craftsmanship. The birth and development of draping (referred to as "3D cutting" in some contexts) have always been deeply tied to tools that simulate the human body. The transformation of draping models—from real humans to standardized forms, and further to digital models—epitomizes the garment industry’s shift from handcrafted couture to industrialization and intelligent manufacturing.

The roots of draping can be traced back to the Gothic period of the Middle Ages. Before that, the "loose garment culture" of Ancient Greece and Rome dominated clothing design: a single piece of fabric was wrapped and tied around the body, requiring no precise cutting, let alone fitting to the body’s curves. However, the Gothic civilization of the 13th century brought a "3D revolution" to architecture—tall spires and transparent stained-glass windows created a strong sense of space, and this aesthetic extended to the field of clothing.

European nobles of that era began to pursue "fitted garment shaping" in clothing. For the first time, the dart—a crucial design element—appeared in garment structure. By gathering and pleating fabric at darts, clothing could fit the curves of the bust, waist, and hips, forming a three-dimensional silhouette. Without existing cutting templates, tailors had to work directly on the nobles’ bodies: they draped fabrics like linen and silk over live models, temporarily secured them with needles and thread, adjusted the pattern repeatedly, and only removed the fabric for cutting once satisfied. These nobles became the earliest "draping models," and this "human-body-centered" draping method laid the core foundation for haute couture.

While draping in the Gothic period achieved an exceptional level of fit by relying entirely on live models, it had obvious limitations: it was extremely time-consuming, required "models" to maintain fixed postures for long periods, and could only serve one individual at a time. Nevertheless, this design philosophy of "directly engaging with the human body" was fully preserved by European haute couture ateliers and became the core technique of the couture industry for centuries to come.

Moving into the Renaissance, the 3D shaping of clothing reached new heights—exaggerated leg-of-mutton sleeves, corseted bodices, and voluminous hoop skirts significantly increased the structural complexity of garments. Although high-end couture ateliers still centered their work around live fittings, they began experimenting with simple "human models": handmade forms shaped from rattan, linen, and cotton, which replicated clients’ body measurements and served as references for pattern preservation and subsequent modifications.

These early handmade draping forms lacked standardization; they were essentially "replicas of clients’ bodies." On the haute couture streets of Paris, France, every established atelier housed dozens of custom dress forms, each corresponding to the body data of a specific client. This "one client, one form" model embodied the exclusivity of haute couture. Even in the 19th century, high-end ready-to-wear boutiques in Europe still maintained the tradition of "live draping + custom dress forms." For example, the House of Worth in Paris became a royal and noble favorite for its precise draping techniques, with its core secret lying in the meticulous replication of the human form.

III. The Industrial Wave: The Birth and Popularization of Standardized Draping Models

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the garment industry ushered in the revolution of mass-produced ready-to-wear. With the popularization of sewing machines and the expansion of consumer markets, clothing was no longer exclusive to nobles—ordinary people also began to pursue well-fitted, affordable ready-to-wear. At this point, the model of "draping on live models or custom forms" became completely unworkable: body types varied across regions and populations, making it impossible to find a live model for every size.

Market demand drove tool innovation, and standardized draping mannequins emerged. Early industrial mannequins were made of plaster and fiberglass, with standard sizes for different countries, genders, and age groups developed through statistical analysis of large sets of human body data. For instance, European women’s mannequins in sizes 36 and 40 accurately replicated the bust, waist, and hip proportions of people in those size ranges, even accounting for the curvature of key areas like the shoulder blades and bust points.

After World War II, the global garment industry entered a period of rapid growth, with clothing companies in Germany, Italy, and other countries beginning to mass-purchase standardized draping mannequins. From the 1950s to the 1970s, the market size of the draping mannequin industry grew at an annual rate of 15%. Mannequin materials evolved from heavy plaster to resin and PU foam, and two mainstream types emerged: slant-pin mannequins and straight-pin mannequins. The former, with a fiberglass core, offered high rigidity and precise sizing, suitable for professional ateliers; the latter, with a softer texture that allowed pins to be inserted vertically, was more ideal for fashion schools and small studios.

The popularization of standardized draping mannequins completely connected the "design-production" chain: after designers completed draping on mannequins, patterns could be directly converted into 2D paper patterns for mass production on assembly lines. This not only ensured pattern consistency but also greatly improved production efficiency, bringing draping technology from haute couture to the mass ready-to-wear sector.

IV. Technological Empowerment: The Leap from Physical Mannequins to Digital Draping Models

In the 1980s, the rise of computer technology brought a disruptive transformation to draping models, and digital draping mannequins began to emerge. Clothing companies in Japan and South Korea were among the first to adopt CAD (Computer-Aided Design) systems, using 3D modeling technology to build virtual human models on computers. Designers could directly drape virtual fabric, design darts, and adjust patterns on these digital mannequins.

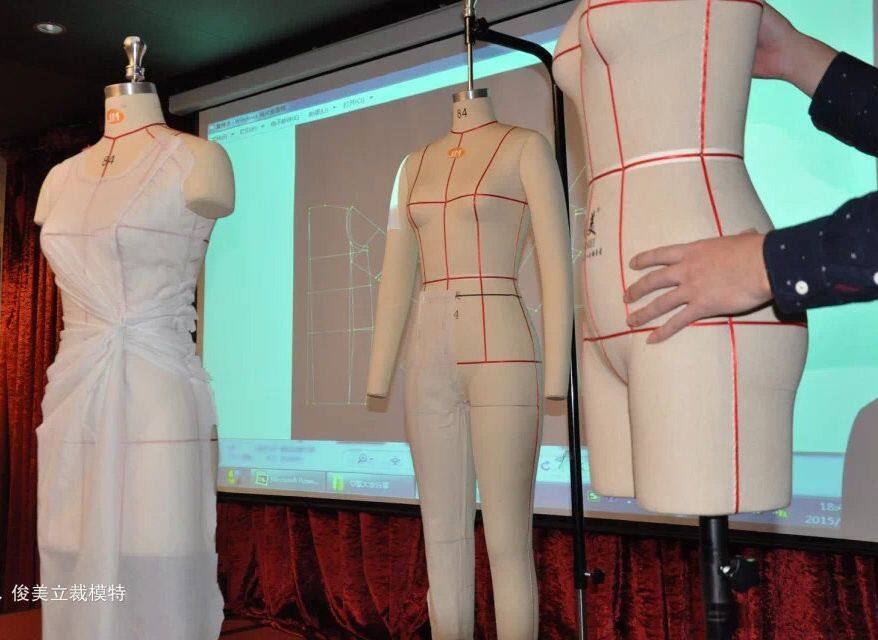

In 1985, after a renowned fashion design school introduced digital draping technology, students’ design works not only saw a significant improvement in pattern precision but also allowed for rapid testing of fabric and color combinations—subsequently, the school’s award rate in international competitions rose sharply. By the 21st century, technologies such as 3D scanning and virtual reality (VR) further enhanced the digital draping experience: 3D scanning of real human bodies enabled the creation of highly personalized digital mannequins; with VR headsets, designers could "immersively" adjust dynamic garment patterns, simulating how clothing moves when the body walks or raises its arms.

The advantages of digital draping mannequins are remarkable: after a clothing company adopted this technology, its design cycle was shortened by 30%, sample production costs were reduced by 20%, and the time from design to market launch was cut in half. Today, domestic clothing brands in China are also accelerating their digital transformation. Since 2015, several listed companies have invested heavily in developing proprietary digital draping systems. From 2018 to 2020, the number of related patent applications grew by 30%, with intelligent and digital patents accounting for over 50%.

V. Symbiosis of Tradition and Technology: The Future of Draping Models

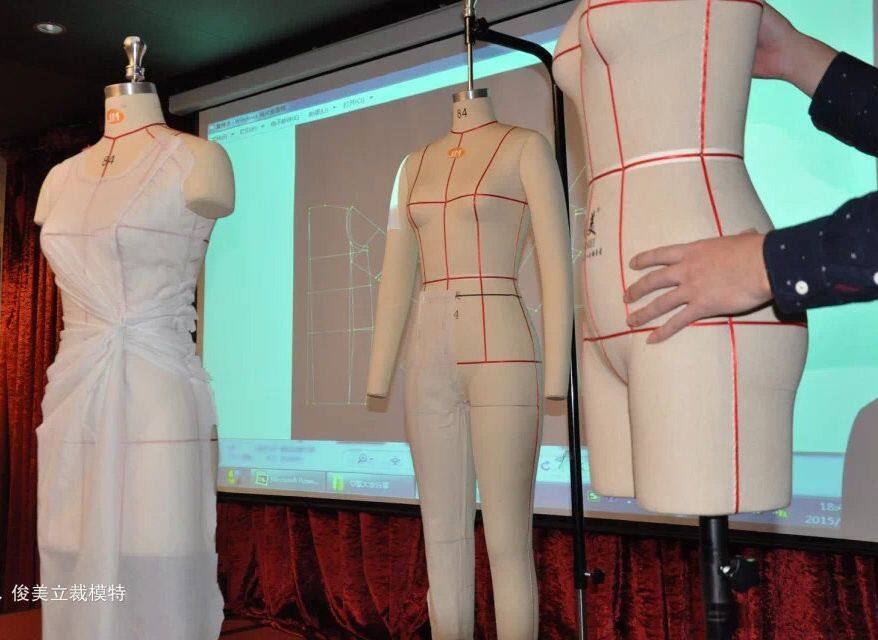

Interestingly, even as digital draping becomes a trend, European haute couture ateliers still preserve the tradition of physical mannequins and live fittings. In the high-couture workshops of Dior and Chanel, designers first complete initial patterns on digital mannequins, then make manual adjustments on physical forms, and finally confirm the fit with live models—achieving a balance between "technological efficiency" and "artisanal warmth."

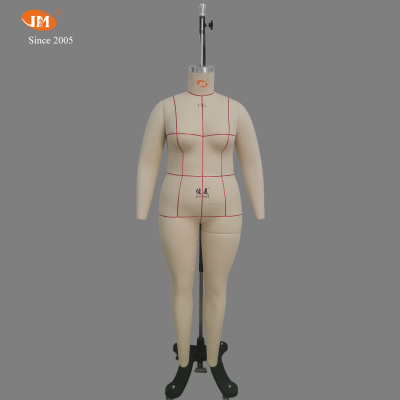

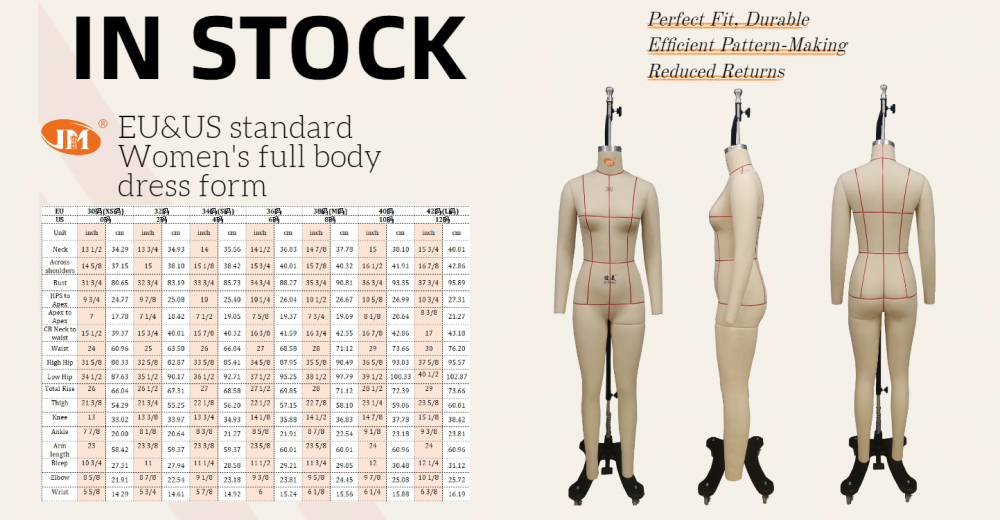

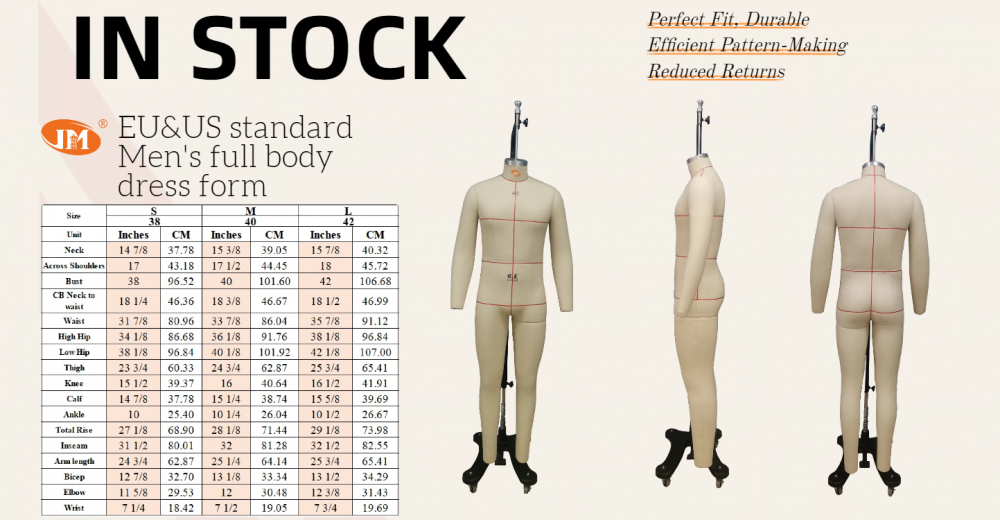

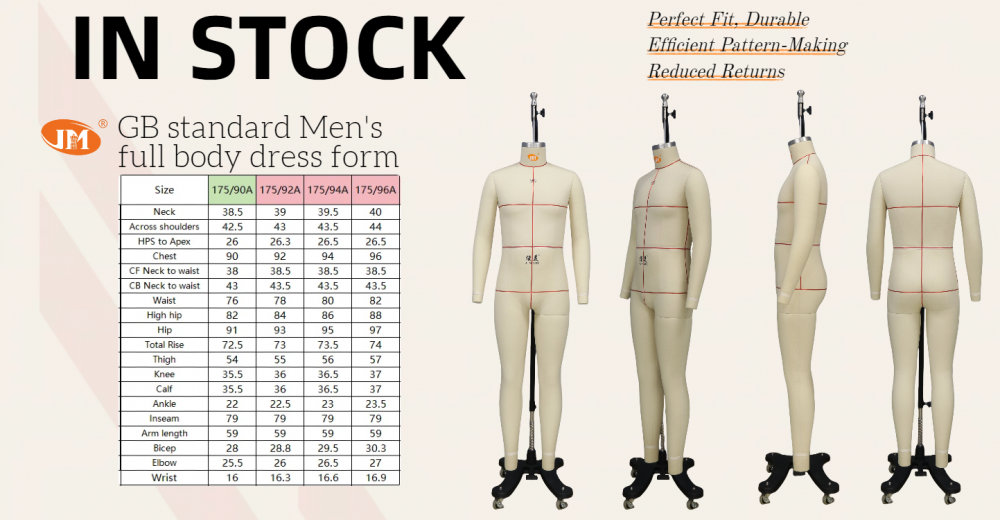

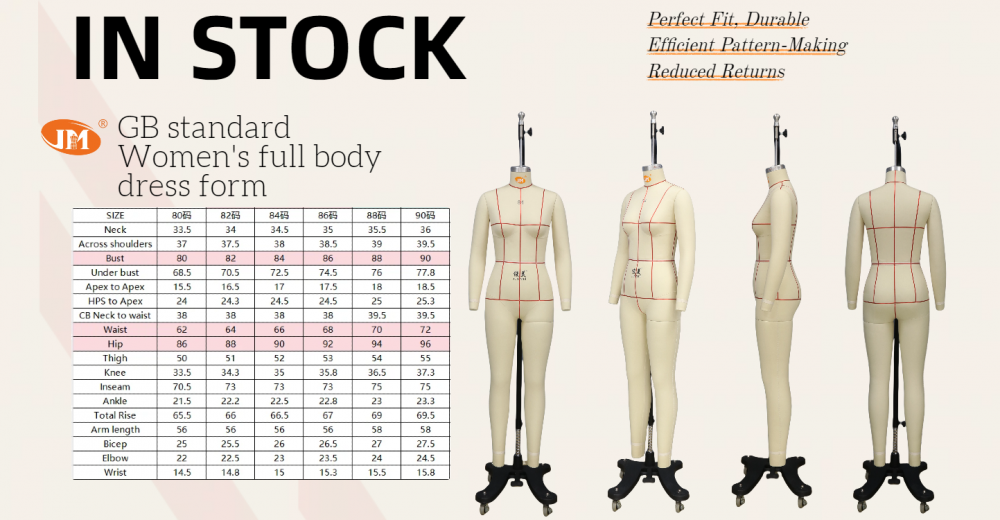

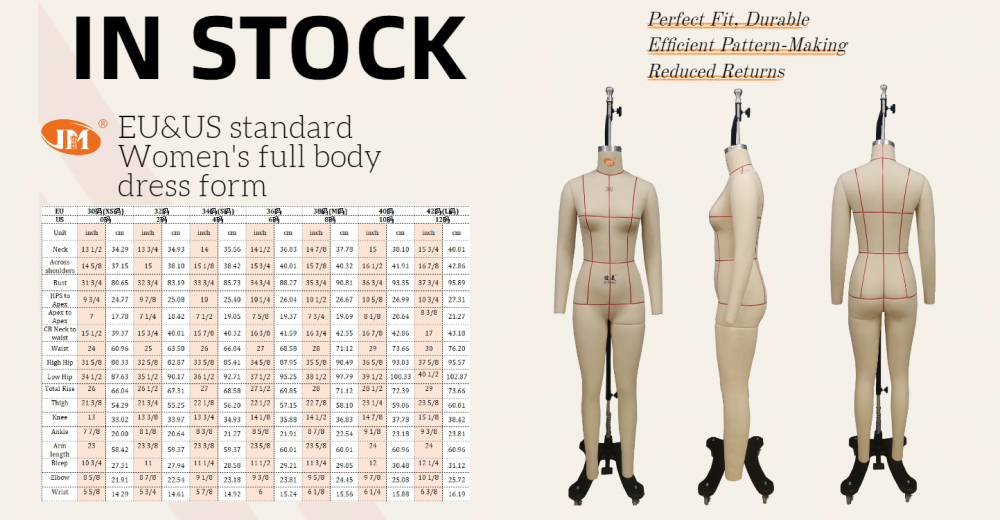

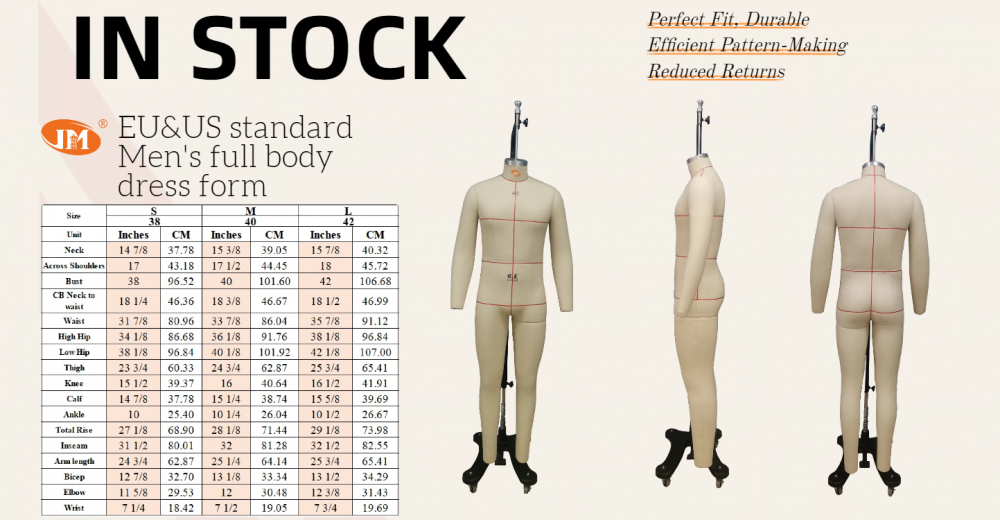

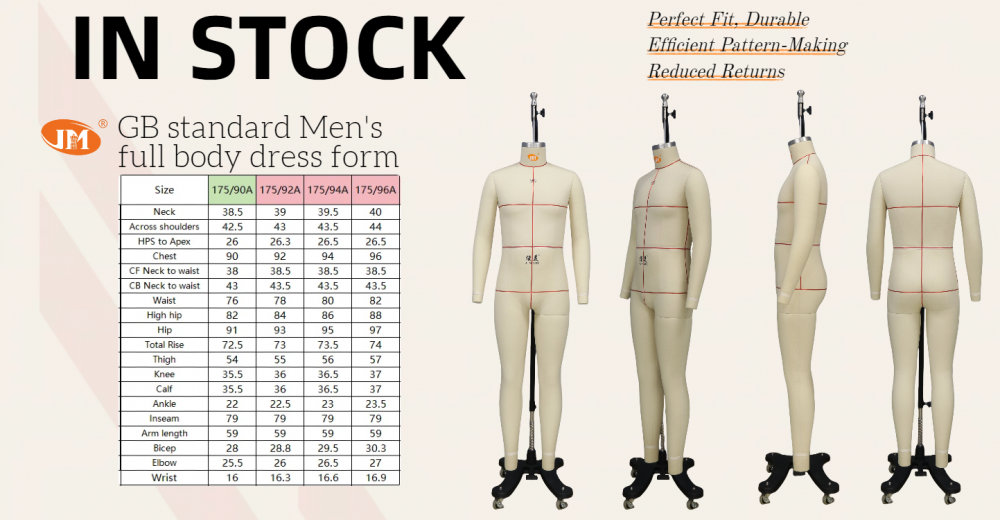

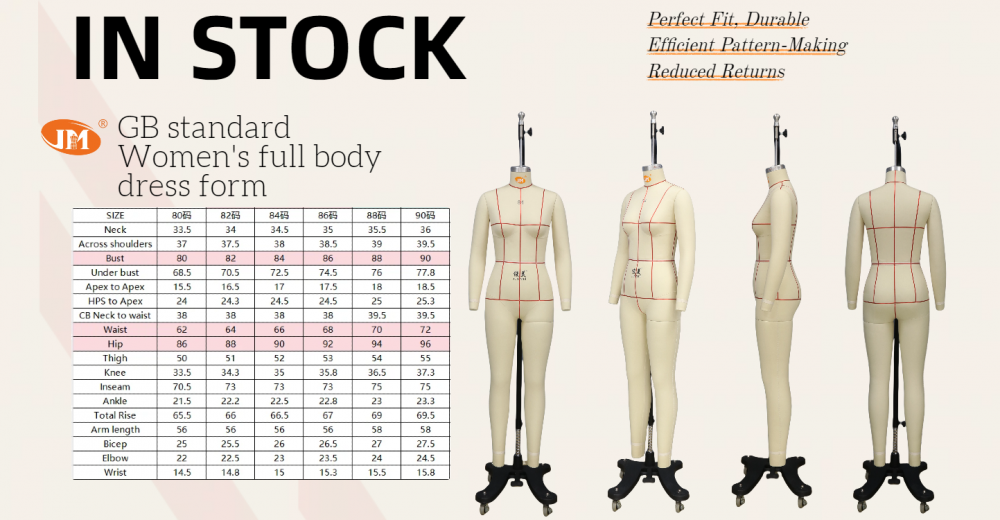

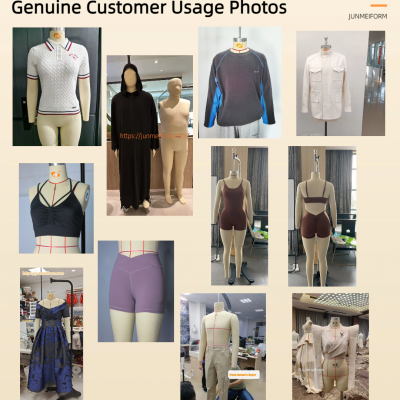

In the mass ready-to-wear sector, "refinement" and "diversification" have become new trends for draping models. Specialized mannequins for different populations are gaining popularity, such as those for maternity wear, sportswear (accounting for muscle movement range), and Asian body types (adapting to the shorter torso and wider hips of East Asians); 【Junmei Mannequins—from industrial standards to customized specialties, accurately replicating human body curves with durable resin material. Suitable for haute couture, fashion school teaching, and mass production, whether it’s specialized patterns for maternity wear or sportswear, or collaborative design with digital mannequins, it enhances both draping efficiency and pattern precision, becoming a professional and reliable "good partner for 3D draping" for garment professionals!】 Meanwhile, the application of 3D printing technology has significantly reduced the cost of custom mannequins, allowing ordinary consumers to own personalized digital mannequins and making "ready-to-wear customization" affordable.

From live models in the Gothic period to handmade replicas in the couture era, from standardized industrial mannequins to today’s digital models, the evolution of draping mannequins is a microcosm of the garment industry’s progress. It has always revolved around one core principle: making clothing understand the human body better, and making design closer to needs. In the future, with the integration of artificial intelligence and metaverse technology, draping models may enter a new era of "virtual fitting + physical production." However, no matter how technology evolves, the original intention of "respecting the human body and serving the wearer" will never change.

Read More

Read More Read More

Read More Read More

Read More Read More

Read More